Archival Washing Tests (Part 1: The Background)

This is the first of a four-part series relating the results of my archival print washing tests.

Background

Properly washing a print is critical for archival permanence. Residual fixer, especially the more typical acidic fixer, will degrade paper over time, causing it to yellow and taking all the highlights in that tonal direction. How much residual fixer is too much, and how long it takes before you can see a noticeable effect are very difficult to quantify, and there are so many variables involved that it would be very difficult to reach a conclusion through theoretical methods that would satisfactorily encompass the range of variables. The changes occur so slowly that attempting to quantify limits through observational (empirical) testing would be an exercise in futility, not to mention we want to know the limits now, not after 50 years when the generation after next starts to notice our prints have turned a bit yellowish.

The simpler answer then is to be certain we’ve done an adequate job of removing the residual fixer. If there’s no fixer remaining, we know we’ve done our best.

I won’t get into the finer points of chemistry involved in any of this, partly for simplicity, and mostly for the fact that chemistry was not a strong subject for me. Really not a strong subject for me.

The most important means of removing residual fixer is a post-fix wash of the print in water. The washing efficiency can be improved with use of a wash aid such as Kodak’s Hypo Clearing Agent. This wash aid is used before the water wash to make removal of the fixer more efficient. The wash aid is held in a tray with the print and agitated regularly.

Print washing methods can take several forms, dependent on space, equipment, availability of water, time, and other factors. The only two methods that I utilize, and therefore the only ones that weighed on my processes and tests are tray washing with a print siphon, and washing in an archival washer.

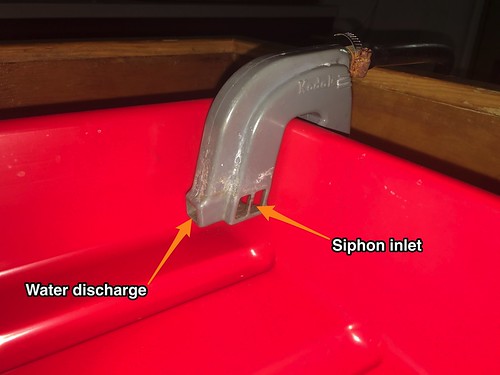

If you’re not familiar with the print siphon, Kodak made one they called the Automatic Tray Siphon. I’m not sure if anyone else made a product similar to this, as I’m only familiar with the Kodak siphon. It hooks on the edge of the tray, and when you get the water flow just right, as it flows into the tray from the inlet it creates a siphoning action that pulls water back out through the device from a different opening, discharging it at the bottom below the tray. It can be a little tricky to dial in — if the water flow is either too much or too little, the siphoning action won’t function causing the tray to overflow. Once it’s running correctly, it works great. Here it is, mounted to a tray.

The photo below on the left shows the water discharge and siphon inlets, and the photo on the right shows the siphon discharge. I try to keep the discharge over the drain as much as possible. The rim around the drain in this sink creates a small dam, so any water not going directly into the drain tends to pool in the sink.

Here’s a video of it in action. You can see it moves a print around quite a bit. The print in the video happens to be resin-coated paper, so it doesn’t get water saturated and stays pretty light. A fiber-based print doesn’t move around quite as much.

Tray washing, even with an effective means of constantly replacing fresh water using the tray siphon, is not without challenges that make it difficult to adequately wash a print. If you’re only washing one print at a time it’s just fine, but that makes the throughput pretty meager, especially with wash times (spoiler alert) on the order of 50-60 minutes. You can wash multiple prints at once, but you have to keep them moving vertically in the stack. In other words, if you’re washing two prints the print on the bottom needs to be moved to the top every few minutes, moving the top print underneath, then repeating again and again. The more you handle your prints, the more opportunity you have for handling damage. If you have more than two prints, the constant work of keeping them sorted will take most of your time during washing and make it challenging to accomplish much else.

My other option is the archival washer. I’ll create a post soon where I discuss the washer I built in a little more detail, but here’s a photo.

The fresh water comes in through the hose on the right side of the washer, and the water is distributed along the width of the washer with holes drilled at spacings to match the spacing in the internal print rack. The hose on the left is the discharge which siphons the water from the bottom of the washer. Since the specific gravity of the fixer is greater than water, it sinks to the bottom from where it’s siphoned. The flow rate of the washer is about 0.4 gallons/minute. The internal rack will hold 11 prints, each in their own slot, so there’s no need to move the prints around during washing. Here’s a photo of the rack.

Regarding the tray siphon, I have to wonder if it performs an adequate job removing the fixer from the tray. As you can see from the photos of the print siphon, the siphon inlets in the tray are well above the bottom of the tray, so it’s not pulling the water from the lowest part of the tray where we’d expect the fixer to be. Although, the water is circulated vigorously in the tray, it’s likely the fixer stays mixed in solution. The constant addition of fresh water means the fixer in solution in the wash tray becomes more and more dilute to the point where it’s probably negligible, so the fact the siphon doesn’t draw from the bottom of the tray is probably not a factor.

Test Method

To determine if there is residual fixer in the paper, you can use a residual fixer test solution. You can make your own if you have the skills and can procure the ingredients. Steve Anchell has a formula for an equivalent to Kodak HT-1a (no longer commercially available) in The Darkroom Cookbook, but since I don’t have the requisite potassium permanganate and sodium hydroxide readily available, I’d rather have a commercially available solution.

I used Photographer’s Formulary Residual Hypo Test. As far as I know, it is the only commercially available product for this purpose. It differs in use from the HT-1a from the Cookbook; HT-1a is used by diluting it, then allowing water to drip off the print to be tested into the diluted solution. If fixer is still present, the solution will change color. The Formulary hypo test is used by placing a drop of solution on the print after it’s been washed and leaving that drop in place for exactly two minutes, after which it’s blotted off. If fixer is still present, a yellowish stain will remain on the print; the more concentrated the residual fixer, the darker the stain. The instructions include this table:

| STAIN | WASH RESULTS |

|---|---|

| No detectable stain | Excellent |

| Faint tan | Good |

| Definite tan | Fair |

| Definite tan to yellow | Poor |

My overall process was:

- Expose a test strip to mark an identifier (in binary, because it was easier than trying to use stencils for numerals)

- Develop in Dektol for 2:00

- * Stop

- * Fix

- * Tray wash with Kodak Automatic Print Siphon

- ** Kodak Hypo Clearing Agent

- * Archival Wash

- Test with Photographer’s Formulary Residual Hypo Test

* Items vary with the given test. I’ll identify those specifics in the later posts with the test results.

** Only used in some tests. I’ll identify those where it was used in the later posts with the test results.

If these processes led to a finished print, that would be the extent of my testing. But I also regularly tone my prints with selenium toner, typically for 3 minutes at a dilution of 1:9. Since Kodak Rapid Selenium Toner contains ammonium thiosulfate which is one of the ingredients in some fixers, inadequate washing after toning presents the same hazard as inadequate washing after fixing. To be sure I know the times required to remove the residual products after toning, I performed additional tests to quantify those times. I’ll list out the details of that selenium toner washing tests in the post with those results.

Conclusion

Even though this seems like a lot of information, it really only touches on the surface of the subject. I’ll address my tests and results in later posts, but if you’d like more details on the technical aspects of fixing and archival washing there are a number of good resources I’d personally recommend:

- Steve Anchell, The Darkroom Cookbook

- Ansel Adams, The Print

- Ralph W. Lambrecht and Chris Woodhouse, Way Beyond Monochrome: Advanced Techniques for Traditional Black & White Photography

Check back soon for the first set of test results using Oriental Seagull VC-FBII glossy paper and Ilford Rapid Fixer.